My short story, “That Kid Who Saved the World One Time”, published in the Spring 2021 issue of SHiFT: A Journal of Literary Oddities.

Archive for the ‘Words’ Category

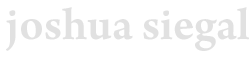

Water at the Top of the World

My debut children’s book, and debut as an art director self-publisher as well.

“A charmingly illustrated children’s book about inclusion and peace-seeking in a world of colliding mythology and science. Enjoyed by religious and non-religious parents and children alike, this book is a great point of entry for discussions on diversity of thought and commonality of human experience.”

Illustrated by Shannon Belock. Layout by Chris Telemann.

Confessions of an Aphrodite Bug

My short story, “Confessions of an Aphrodite Bug”, published in the Fall 2017 issue of Michigan Quarterly Review.

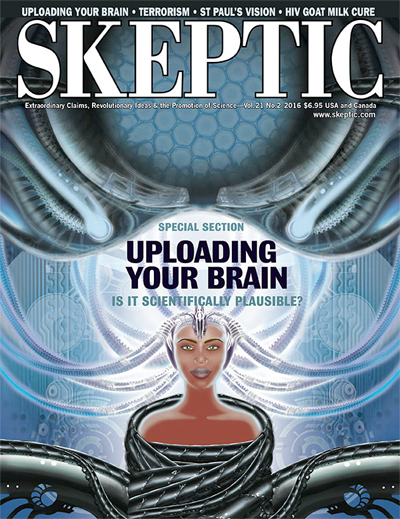

Essay: In Defense of Anti-Science

Published in Volume 21, Number 2 of Skeptic Magazine.

It’s obvious that technocracy will have a place in future human society. As we squelch anti-vaxxers and climate-science deniers, we must be very careful that we also provide sturdy avenues for public feedback on emerging technologies, lest we let technotopia slip into just another form of fallible human oligarchy.

You can read a version of the article on my medium account, as the version in Skeptic is behind a paywall.

Review: David Bowie Is

http://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/bowie-is-at-mca-chicago/3090

David Bowie Is

MCA Chicago

By JOSHUA SIEGAL, NOV. 2014

It was nearly not so. Bowie was not the drug of choice for this show; he was merely what the next guy at the party had a good supply of. Geoffrey Marsh, of the Victoria and Albert Museum who first put together this show, admitted as much quite candidly during his press preview with the MCA’s Michael Darling. The V&A had originally wanted another global rock superstar as the subject of this show, he who for legal reasons must not be named. That show fell through, and was shelved, until the opportunity to work with Bowie’s archivist came knocking.

It has long ago been proven that art can live and breathe on the Rock and Roll stage. With the David Bowie Is exhibit, the MCA Chicago and its partners attempt to prove not only that the reverse is true but also that a well-scaffolded marionette show can bring Rock and Roll detritus to life.

David Bowie Is must certainly be a coup for the MCA Chicago, at least financially speaking, but we probably won’t hear anyone in London, Paris, or Berlin crowing about seeing the names of their cities listed alongside the others. Chicago considers itself a global metropolis, but, with its second-city neurosis, it often acts a bit like a backwater “world-class city,” one that feels compelled to proclaim itself such. The triumphalism of the press surrounding the MCA exhibit reveals a lot about the state of modern art in the “Paris of the Midwest”.

London: Bowie’s birthplace, capitol of his native country, backdrop for his nascence.

Berlin: adopted home and locus for a period of Bowie’s creative reincarnation.

Paris: a fashion mecca.

Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is where this exhibition properly belongs, stylistically and contextually. If the MCA dreams of repurposing an entire floor as the North American Museum of the Natural History of Rock and Roll, this show would be a winning shot across the bow. If it intends to remain the Museum of Contemporary Art, then we must be content to let them cough into their sleeve and collect the admissions fees.

Cultural history transplants rather shamelessly to disjointed locales. This is unabashedly a collection of artifacts, which – though presented chronologically – tries to reassure everyone that it’s not a retrospective. When the remains of Tutankhamen came to this city, they were appropriately hawked for viewing not at the Art Institute, but at the Field Museum, alongside dinosaur skeletons and Native American dioramas.

MCA patrons of the Bowie exhibit will breeze past a small and completely free chamber of dangling Calder mobiles, straight into the maw of an expensive synesthetic leviathan. This is not to say that the show – as spectacle – is unworthy of the door price. Technological plumage can be expensive to display, and in this, perhaps, the show finds a kind of conceptual match: Bowie was a technological innovator – this show is innovative. Get it? But what plumage – location-aware headphone sets allow the visitor to experience an audio scape digitally cross-faded, tailored to his or her personal wandering proclivities (running haphazardly through the exhibit space produces a fantastically surreal live audio piece, though one not endorsed by the security staff.)

At this, the matter and presentation are expertly married: what better subject than a musical icon of the video age, to pair with roaming audio technology? Interview snippets blend through the various zones with recorded music, which itself reveals as synced video soundtrack, but only as the video comes into view. There is much to absorb here in exhibit-craft. Banished is the over worn “video bench” where tedious pieces loop at length in a tomb: no video among the many on offer lasts longer than three or four minutes, all of them nestled in some larger context. Digital media leaps from and winks at glass-cased artifacts from its own past: Bowie’s handwritten notes, sketches, storyboards, and paintings. Well-placed mirrors render interlaced 1980s videos into appropriately trippy dimensions and a recreated studio room cascades talkback ghosts and out-take voices down through the space. The viewer is like an ant wandering on a circuit board inside the head of robot Bowie, stunningly attired in one of his glittery costumes.

The culminating interdisciplinary face-stuffing of the exhibit is a room that splashes together live concert footage, a novel 3D sound experiment that attempts to recreate audio immersion in said concert footage, a stand of theatrically garbed mannequins, stage plotting dioramas, rock show lighting, and video montage. This is the grand finale of the fireworks show and it doesn’t quite come together, but it’s effective in the same way that being vomited on by a loved one is effective: undeniable, and hilarious to the degree that it’s somehow pleasant – it’s Bowie overdose.

So the exhibit really is the exploration of the real history of a fake persona, which was almost a completely different real history of a completely different fake persona. All dealt out with extreme care and precision. What a happy accident that the eventual subject was such a technologist. Maybe there is some resonance here with Bowie’s use of oblique strategies? Maybe Bowie’s references to McLuhan are eerily prescient, in that his personas have been supplanted in this exhibit by the medium, namely the exhibit itself? Maybe this all belongs in a contemporary art museum after all, if we are prepared to accept an ossification of contemporary art, that it will already start listing toward its own past, and turn into the visual corollary of jazz.

For anyone interested in how multidisciplinary installations come together, this exhibit (and perhaps the film that’s already been made about it) should be worthwhile and indeed exemplary. For anyone interested in the relatively narrow topic of the expansive history of David Bowie, this show will be a delight. Those who hold out hope that modern art can continue to thrive and churn without huge influxes of cash will come and gaze at this exhibition with horrific appreciation – like a rockabilly daddy-o witnessing Ziggy Stardust emerge from a limousine.

Review: In Decay: Stitching America’s Ruins

Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art, August 2012

Eric Holubow and the Presumed Descent of America

Amid hand-wringing and finger-pointing over the presumed descent of America sits Eric Holubow’s photography, nestled into a corridor at the Chicago Cultural Center, as summer tourists stop by to gawk at the pristine renderings of tragic architectural wrecks. Dentures out, wig mislaid, houserobe open, arcing in some graceless pose, these structures hold their pride in dilapidated openness, grateful to be sought before the final collapse. From an architectural (though not technical) standpoint, Holubow is Paparazzi in the nursing home.

The work has been seen by many – including the artist himself – as emblematic of a cultural autumn, or mutely damning exhibits in some prosecution. The title of the CCC showing is “In Decay: Stitching America’s Ruins”, and the metaphor is accurate in that the works indeed form a coherent whole, a fabric felted of fraying scraps. But this is not simply socioeconomic documentary photography, Holubow is not merely an archivist, and he seems in his writing to neglect his collaborators, namely the great forces of Nature and Time, as if the gorgeous forms he captures were scandalous social narratives and not irreplaceable works of generative art.

What is the difference between generative art and what we might call (with a wink) degenerative art, the art of decay? In both cases, the artist’s control is in the parameters, and at this, Holubow proves able to set his frame with great sympathy and circumspection, and in many of his images, you can feel the labored breaths of these once-ornate cavities. In “Prison Block”, a shot inside a Tennessee prison so onerous that a state law was passed forbidding its use, a single pole unevenly bisects the frame, rising to the peeling roof, and Holubow’s lens distorts the cellblock rails so that they curve away, both opening and compressing the space, lending action and intimacy to what must be oppressively drab rectilinear environs.

Sharing space with “Prison Block” in the exhibit is “Nuclear Potential”, a squat concrete cylinder viewed from within its circular enclosure. The photograph has a quite static composition, but it is electrically alive. Moss of a radioactive comic book green lingers innocently as rebar twists skyward above the never-completed reactor housing. Short, empty pipe ports gesture to nowhere. Cut through the curving concrete face is a perfect square, and through it we can stare past its opposite at the back of the enclosure. In many of the pieces in “In Decay”, Holubow presents us, center frame and sitting quietly at the rear, with a door or window we might not notice at first glance.

One such door greets us as we face laterally across Gary Indiana’s Palace Theater, on a balcony edge which curves away and back again to the middle of the frame. Above, the blue-tiled roof has some blotchy disease. Below, a drape with a faded Mediterranean scene still hangs gamely from the proscenium. All of the seats on the main floor are scattered and flattened in a delicious array of scalloped orange forms. The orchestra pit is shamefully exposed, made up in white dust. Above, set into the middle of the opposite wall, a story above the floor, sits the intriguing little door. It is easy to imagine that it leads mischievously to a straight drop down the exterior of the building. Holubow does not show us any exteriors, but these doors and windows cunningly featured hint at a way out – maybe, for the artist, at rescue?

More overt are the beams of light which Holubow captures blasting through cracked stained glass, or else spilling through fissures in ceilings. These luminous interlopers are unnecessary, especially in the case of the many religious interiors captured in this show. The world is littered with religious structures in all states of disrepair, and though their plight is moving and their interiors often gobsmacking, the artist edges disturbingly close to postcard elegies with some of those shots. Part of western religion itself is the tension between the ever-denuding material world and the promised lofty constancy. There is more pathos in the show’s degraded utilitarian spaces.

In a ruined Detriot apartment building lobby, a single chair ignores a baby grand piano pitched forward on its face, its lids open to eternity, its keys unevenly serrated like a player piano frozen in action. A lonely textbook rests in an abandoned classroom, where graffiti decorates the chalkboards and the ceiling has flaked down to cover the children’s desks in with a scatter of serene paint chips, and the cathode-ray television set above on the wall is pristinely preserved. At the Packard Auto Plant, saplings thrive under the angled glass factory roof, which looks out like a wrenched-open greenhouse on acres of drab green farmland. These are the better moments – and they are moments – as many of the structures featured no longer exist.

The exhibit begs to draw us into this chronology, with flatly described histories posted next to each photograph; though interesting, these statements do not explain or improve the resonance of the pieces, which lies in the physical and anthropomorphic subjects and the gentle, accurate care afforded them by the artist. Given the tendency to see ourselves in our constructions, we might connect this exhibit with an inhumanity, a callousness, but sympathy for victims is insufficient: to a photojournalist, there is a story. If the story here is the sorry state of neglected eastern American buildings, then we have some entrancing assets for the local paper’s editorial page. But there is more. Take, for example, the medium-size prints of these cavernous spaces. In resisting the urge to render them in large format, Holubow gives us two dimensional dioramas, into which we peer at characters who are works in progress.

The grainy facade of the imposing dome in a New York tuberculosis hospital is pitted with bits of color, as if a pixellated projection were fixed on its surface, while at its center a stately, radially symmetrical, and quite intentional piece of stained glass stands ground amid the noise. In another piece, a five-part tapestry of windows reveals the tableau of their exterior, a skeletal, rural backdrop progressing to the new commercial, the building itself observing its own past and unreachable once-future. All this is seen in random keyhole hints, through spattered patterns of fractured industrial glass.

In gnarled rebar and capricious splays of lumber, we see the human hand, but the human hand removed. In its place step the natural forces, firm and sure, sparing parts and laying waste to others, as chaotic, detailed, and grandiose as the best code art iterations, and infinitely more expressive. Our senses themselves follow such natural patterns, in nerve endings and optical cones and the tangled improbability of our brains. Whether one prefers the sublime proportions of classical architecture or pulsing organic forms, the clash of these impulses informs everything aesthetic, and it is this clash – not economic decrepitude, not cruel neglect – which humbly animates Holubow’s photographs.

Then we walk out from the exhibit into the exquisite foyer of the Cultural Center itself, and eye the stonework and glittering mosaics, and wonder if we’d wear the same aesthetic blinders, were this luscious public landmark – with its crown, largest Tiffany dome in the world – to appear in one of Holubow’s photographs, and itself become a piece of future wreck-porn, and we think then again, maybe Holubow has a point.

Published in Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art

Review: Chipaumire & Mapfumo at the MCA

Whitehot Magazine, October 2009

Nora Chipaumire with Thomas Mapfumo and The Blacks Unlimited @ MCA Chicago

“Welcome to Zimbabwe.”

Where the rains fall in computer-generated light projections? Where Wolfgang Puck desserts are sold in the hallways? Where Chimurenga music plays, and the only dancing is choreographed?

No, this statement stakes a claim. Nora Chipaumire, her legs rooted downstage, upper limbs slapping, unfurling, proclaims through her teeth today’s interest rate: one million percent. Then, she issues a dare. “Life is good!” Desperation, conviction, and joy fight silenty in her posture. Her vocal outbursts claim the prerogative of perspective. This is a catharsis, not a travelogue.

Behind her, the legendary Zimbabwean band, Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited, sit among their tiny amplifiers and pluck at their instruments. Around them glow unfrosted lightbulbs, the naked filaments dancing and sputtering. The band could be sitting on their suitcases, near an airport tarmac or playing impromptu at some kind of depot. The towering, flat brick backdrop of the MCA Stage is any brick wall, and it renders to the musicians a human scale. They wind their lattice melodies out through the space and retract them with expert dynamic control.

The dancers, Chipaumire and her partner, Mallory Starling, appear and immediately begin taunting with their cleverly designed torn jackets and dyed dresses. Flip up some cloth and hide my face. Flip up some cloth and show you my ass. They are teasing dance traditions and identity art from within, but not in the winking, self-aware way – there is too much ground here. Starling and Chipaumire show off strength and poise, but their movements, choreographed by Chipaumire, express a freedom that is belied by rare and rewarding moments of unision. In one piece, Chipaumire spends almost the entire song framed in a block of white light against the brick, gazing down, while Starling contorts plaintively in the foreground. This is high identity, saying at once: let me expose for you the brutality of my cliche, and by the way, isn’t life good?

Unlike so much political art, there is no manufactured, small-batch emotion. These are real revolutionaires; Mapfumo was the musical voice of the revolt that birthed Zimbabwe in 1979, and also the musical voice who exposed the corruption of his once-hero Robert Mugabe, leading to the singer’s self-exile. Mapfumo, The Blacks Unlimited, and Chipaumire all seem caught in the same expatriot glare.

Chipaumire steps forward out of her own silhouette and lifts her companion from the ground. Digital rain falls against the brick. She tries to elevate Starling but cannot. They perform a limping, grasping waltz, while Mapfumo and The Blacks Unlimited unravel melancholy protest rhythms. Everyone is leaning on everyone else, dancers and musicians alike.

The performance, a world premiere collaboration, features a melodramatic profusion of fog machine and some digital projections that, while proficient and occasionally engrossing, dangle off the edge of the rock concert ethos. This is a modern dance and musical performance, but it is definitely not a rock concert, not with Chipaumire’s energy dominating the intimate space. Still, the technology that hums through every aspect of the performance is fitting, thematically: Mapfumo was the first to render traditional Shona music in electric instruments such as the Les Paul guitar that sits in his lap all evening.

For the polyrhythmic complexity of their music, Mapfumo and company are overwhelmingly still, physically, almost hunched. They give off not the proud air and studied quietude of classical musicians, but the bared conspiracy of an opened plant bud. They are sitting in a straight line but playing in a circle. The dancers contort at their flanks. Chipaumire has one leg planted, the other extended at a perfect angle. Her torso winds and dips. The music turns through its self-iterative loops. She turns to stomp at the ground, an exultant smile on her face. Gems of sweat drop from her head, through the light, and splash the stage.

In fairness, it must be asked, is this just another well-performed curiosity, exoticism playing with modern lenses? But then it must also be asked, in fairness to whom? The genuine has a lovely habit of adopting any mantle it chooses. In their first collaboration, Mapfumo, The Blacks Unlimited, and Chipaumire have established the vanguard as their baseline. In bringing their art to the world, they face off in a common future, for better or worse.

Published in Whitehot Magazine

Review: Temple Exercises

Whitehot Magazine, February 2009

Theaster Gates at the Museum of Contemporary Art

What happens when an endurance piece fails to endure? When minimalist music halts itself and bargains with the audience? When race politics steals from other cultures? Theaster Gates and his friends, the Black Monks of Mississippi, bravely stepped up to these questions in their MCA installation/performance, Temple Exercises, and just as bravely backed away. Gates is not afraid to leave questions unanswered, but this is not the same thing as presenting the viewer with engaging, entangling conundrums.

Instead, Gates et al. erect a house of opaque mirrors, and that in itself has a certain resonance with the piece’s overtly zen-magical-religious aspects. A koan: what is the sound of scores of art geeks refusing to murmur? We nearly had an answer. The performance itself featured Gates, seated at a microphone in his wood-palette temple, joined by an uncredited (in the program, anyway) Leroy Bach on guitar and Jayve Montgomery on saxophone. Gates played the part of guru-MC, gamely cajoling the audience to join him in his meditative Oms. The response was meek and timid. Another question introduced and then abandoned by this piece: when the line between witness and participant disappears, what replaces it? The performance ended before seriously trying to find out, with Gates acceding to his audience’s request to be more or less left alone beyond the fourth wall of the minimally but intensely decorated space.

Underlying the discomfort were some sucesses: the shuffling together of Black American history and Zen religion produced some smart steps and rich harmonies. Particularly sharp, and deserving of its own series or gallery space, was the arrangement of two black iron shoeshine steps back-to-back, forming a striking totem that conjured for itself a dual identity as some symmetrical character of Eastern language. Adding warmth to the vibrations of the performance were wood tiles that covered every inch of wall and surrounded a tower of architecturally stacked palettes, creating the temple space for the performance.

All of this was waiting to resonate, and it fell to Gates to stir up a sound that would suffuse the space and draw together its disparate entities. As Bach and Montgomery wove noodling mantras with their instruments, Gates played gospel preacher to his chorus of reluctant disciples. “Real big breath, y’all!” A few self-conscious voices rose from the floor, and Gates, sitting above us on his chair, saw comedy. Perhaps a performance is a happening not coming into being. Gates himself merged a churchy vocal tenor with shades of throat-singing; the interplay of his vocals with the other instruments generated a truly satisfying resonance with the wood facades. Yet, even Gates admitted to his audience, a bit wryly, that at this show, he didn’t “convert nobody”.

None of this can be fairly considered without acknowledging that Temple Exercises is part of a larger, longer, ongoing collaboration between Gates and the Black Monks. But why bring this series from the dance club and the shoeshine store into the museum? Surely, this performance was evidence of an art gallery’s tendency to suck the life out of music, and thanks to the wood application on the walls, we can say that this is not purely an acoustic phenomenon. If it was Gates’ intention to turn this phenomenon on its head, he let his audience get the better of him.

Visually, the spare installation merged well with the various pieces of audio gear, gongs, and sadly under-represented spontaneous ink-paintings that were part of the performance. As a visual-sonic installation that could be explored by wandering patrons, the space may have had more power. As it was, the personality of Gates competed a bit too much for attention. This posed and left unanswered yet another question: can identity art work as diffused individualism? Would this piece have been shown if not for the growing renown of its practioners?

And yet, the empty ethos of zen saves Gates, in a way. If he is leaning on it as a crutch, he is leaning on an absence. If he is wielding it to dab extra colors onto his cultural tapestry, he is using invisible ink. This is a powerful yet inscrutable wall to hide behind. Simply contemplating the blues howl verging into the effacing zen pedal-tone chant could lead one into a deep historical, cultural, and artistic meditation. But Gates wants to shake your hand while you’re meditating.

As a musical performance, “Temple Exercises” looks better than it sounds. As a piece of gallery art, it sounds better than it looks. As a multicultural monk who deals in questions and meets investigation with mere smiles, Gates is the perfect part.

Published in Whitehot Magazine.

Review: Chris Ware at Carl Hammer

Whitehot Magazine, May 2008

Chris Ware at Carl Hammer Gallery

Chris Ware, Rusty Brown — Chalky White; Life so Far. 28″ x 20″ 2002. Detail.

Chris Ware has developed a following for his cartoons that seems based on his ability to take the Beat-comics angst of Art Spiegelman and the endearingly vacuous expressions of Little Orphan Annie and recast them into spare, if vividly coloured, geometrical drawings that appeal to contemporary ennui. His current show at Carl Hammer Gallery strips the pixel applique off this work and reduces it to fairly architectural blue-pencil and ink structures on bristol (and under glass). In such a display, the blue-line underpinnings vibrate and breathe, the inked sections reveal the strength of Ware’s hand, and, in the in-betweens, the artist bares himself.

The show is cashing in on Ware’s artwork as such, turning production drawings into gallery pieces. It begs the buying community to place its trust in Ware’s continued rise or enduring cache. Notably, Bill Watterson’s collection of pencil-and-ink drawings, together with their coloured-in counterparts, made up Calvin and Hobbes: Sunday Pages 1985–1995, published as the catalogue for an exhibition at the Ohio State University’s Cartoon Research Library. Ware’s exhibit, his tenth solo show and second at Hammer, continues to position him within the borders of the art world, if not necessarily the annals of cartoon history. Only time will tell whether his drawings will take a place along with Disney or Chuck Jones cels, and whether they are to be properly regarded as works of art or as collectors’ items. In the meantime, there is a lot to be gleaned from these comic-strip skeletons on display.

Chris Ware, Building Stories — Room 2. (McSweeney’s.) 29″ x 20″ 2003. Detail.

Chris Ware, Building Stories — Room 1. (McSweeney’s.) 29″ x 20″ 2003. Detail.

Ware colours his ink drawings digitally, imparting a precision of colour and tone. Without these visual and thematic enticements to the work, we are left with the story of an emotionally undulating draftsman possessed of a steady hand and amiable cartoon style. The stories are pomo-emo graphic novel bread and butter: characters bravely assert their individualities in the face of crushing anomie, often making the struggle plain only in their own imaginations. They mull the ironic taste of seasoning deep depression with grains of hope. They bare all this in long, journal-style narrative text blocks, or suffering silently in time-lapse panel arrangements.

But enough on content. The real story in this exhibition are the blue lines humming along under the threads and masses of black ink. There is a particular emotional content to the extreme care and visible revisions revealed by the penciling. Lines run through panels unexpectedly, phantom objects linger close to the bristol, angles are drawn and redrawn. Given the emotional density of the narrative, evidence of such attention animates the drawings in a way that polished digital cannot. It is easy to imagine Ware hovering at his drafting board, lavishing over his drawings as an obsessive child paws a worn stuffed animal for comfort.

Chris Ware, Building Stories — Abortion 2. 29″ x 20″ 2007. Detail.

And then, he turns and winks at you. A judicious application of white ink would easily have erased the litany of scrawled blue notes in the margins of these works. Instead, Ware has left them; tantalizingly, it is often unclear whether they are bits of cartoon character thought or jots to himself. Some of the scribbles are obviously simple notes, as many of them are actual phone numbers. I tried calling almost all of them, standing right there in the gallery. In a way, it was heartening to know that Chris Ware had called Earthlink Tech Support at some time while working on a particular board. Or that he at one point had a connection with a Chicago’s Prosser Academy high school, room 203.

It is hard to believe that an artist would leave such details on a work-in-progress installed for display. Perhaps this is a digital-age response to the unceasing flow of produced images; you want authentic? Read right here about how my cat suffered a stroke after I finished this panel and was put to sleep. This could be the visual analog to the trend of including studio demo tracks as bonus material on record album releases.

Chris Ware, Building Stories — Day (Dinner.) 20″ x 25″ 2007. Detail.

Chris Ware, Building Stories – Rich part 2 (original drawing)

Ink and blue pencil on bristol board,

20 x 29 inches, 2004, Detail

In his blue-pencil closed-circuit conversation with himself, Chris Ware notes in the margins: “SYMPATHY! Avoid being histrionic with gestures.” “I can’t believe I [himself? a character? both?] ever had any pretensions of being a writer.” And the enigmatic “the power of”.

In the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, you can view, framed in glass, the first page of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson’s manuscript from Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas, complete with his own blue-pencil revisions. Ware’s exhibit at Carl Hammer Gallery reads like a non-linear version of this, with the artist’s life pressed in a collapsed scaffold of blue and black. As a biographical document, it is stunning.

Published in Whitehot Magazine.